Author:

PRITTA RATNANINGTYAS, S.Psi

BACKGROUND

The revitalization of family planning (FP), through the implementation of program, or better known for its Indonesian abbreviation Bangga Kencana, aims to enhance the engagement and ownership of regencies/municipalities to the program. To that end, Bangga Kencana established a comprehensive and integrated management model together with the program’s implementing partners and other stakeholders. As one of the provinces of 35 regencies/municipalities, Central Java has a pivotal role in the success of the national Bangga Kencana.

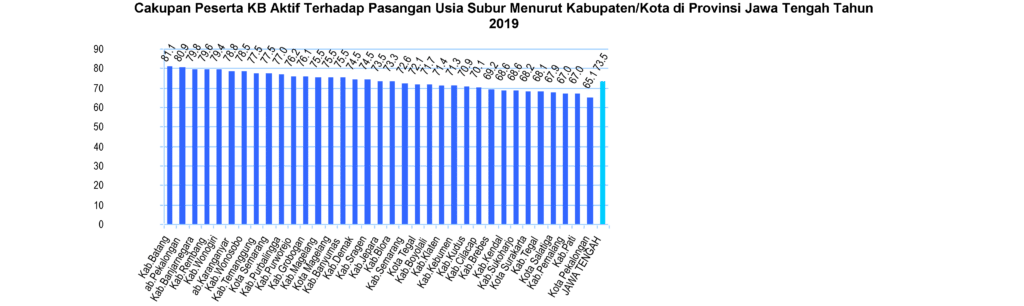

In 2019, the contraceptive prevalence rate (CPR) of Central Java stood at 73.5 per cent, which was a slight drop compared to 73.7 per cent in 2018. By regency/municipality, the areas with the highest CPR were Batang Regency at 81.1 per cent, followed by Pekalongan Regency at 80.9 per cent, and Banjarnegara Regency at 79.8 per cent. Meanwhile, the areas with the lowest CPR were Pekalongan Municipality at 65.1 per cent, Pati at 67.0 per cent, and Pemalang at 67.0 per cent (Central Java Health Profile, 2019). Surakarta Municipality, Central Java’s densest area, had 68.2 per cent CPR in 2019, or lower compared to the provincial CPR.

The National Population and Family Planning Board (BKKBN) 2019 performance report on Central Java showed that the province’s Total Fertility Rate (TFR) stood at 22.3. In Surakarta Municipality, TFR stood at 1.8. TFR indicates the average number of children a woman may have throughout her fertility cycle from 15 to 49 years old. Regional TFR is useful in demonstrating a region’s social economic development progress. A high TFR reflects an averagely young age at marriage, low education attainment, and low socio-economic level or high poverty rate; at the same time, TFR may also reflect the progress of FP intervention in the region (Khusniyah, 2015).

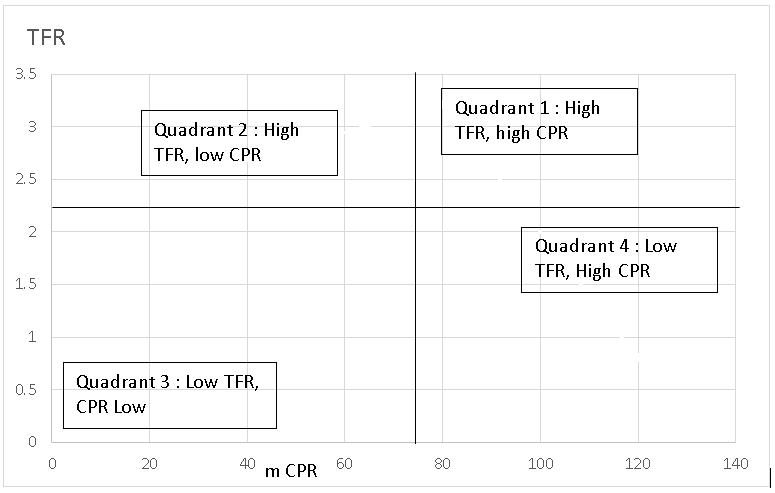

According to the fertility theory expounded by Bongaarts, CPR is inversely proportional to TFR. The increase in CPR contributes to the reduction of TFR, as seen in the following TFR-CPR quadrant.

The above quadrant can be used to map provinces regencies/municipalities based on their CPRs and TFRs while placing the national/provincial TFR and CPR along the axis. Looking into the data of Surakarta Municipality, Surakarta has low CPR and low TPR, a combination that we can call as data anomaly. In the same vein, a study conducted by Wilonoyudho, et. al., in 2018 also found that Pekalongan Municipality in Central Java had data anomaly of low CPR and low TFR.

Further research is required to explore the anomaly and to tackle the situation through Bangga Kencana. This paper therefore aims to discuss and recommend solutions for the anomaly in Surakarta through Bangga Kencana.

RESULTS

Study results showed that Surakarta Municipality had 68.2 per cent CPR, which made Surakarta as one of the municipalities with the lowest CPR attainment compared to provincial CPR. The following figure shows CPRs in Central Java in 2019.

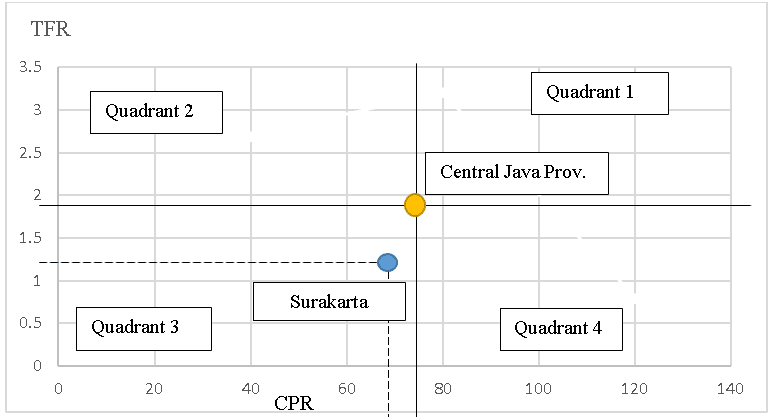

According to BKKBN 2019 performance report on Central Java, the province’s TFR stood at 2.23, while Surakarta Municipality recorded a 1.8 TFR. In this case, the low CPR was not inversely proportional to TFR; in contrary, there was a direct proportionality where low CPR was followed by low TFR.

According to Bongaarts, the increase in CPR should affect the reduction in TFR, as seen in the TFR-CPR quadrant (Andini and Ratnasari, 2018). Surakarta Municipality is in Quadrant 3, where both CPR and TFR are low – also known as anomaly quadrant.

DISCUSSION

Our study revealed that the anomaly of FP intervention in Surakarta was observed in the municipality’s directly proportional TFR to CPR. The following figure shows the analysis of low TFR and low CPR in Quadrant III:

The application of quadrant analysis in the design of strategies or next-steps that build on a program’s success is one of the approaches in determining an effective intervention strategy. In this case, CPR increase and TFR reduction are part of the key goals of FP interventions.

The PMA2020 survey results in 2015 showed that CPR, for all kinds of contraceptives, was higher in rural compared to urban areas (62 per cent compared to 60 per cent). Similarly, modern CPR (mCPR) was higher in rural compared to urban areas, with rural mCPR four per cent as high as urban mCPR. Moreover, the prevalence of traditional contraceptives was higher in urban areas compared to rural areas (Resti Pujihasvuty, 2017). In other words, the urban CPR, overall, was lower. This was consistent with this study’s result that grouped Surakarta Municipality as one of six regencies/municipalities with the lowest rate of FP participation.

There are different factors that influence FP coverage and participation in an urban setting, including the level of education attainment. The majority of couples of childbearing age who reside in urban areas have higher education level. This was argued in a study that stated that contraceptive use declined in women of childbearing age with high education level, i.e. those who earned college or university degrees (Resti Pujihasvuty, 2017). Occupation is another reason for women to avoid contraceptives; the insertion of contraceptives such as IUD and implants is perceived to be an obstacle for women’s professional performance at work. Another factor is socio-economy. The study conducted by Resti Pujihasvuty in 2017 mentioned a survey carried out towards urban respondents that showed that groups with higher socio-economic status had lower FP participation rate. Data-wise, the use of traditional methods of FP is one factor that may show low FP coverage, as traditional methods are not reported in routine statistics reports.

TFR that directly proportional to CPR in Surakarta is a phenomenon known as data anomaly. This was in line with a study conducted by Saratri Wilonoyudho and Sucihatiningsih Dian Wisika Prajanti in 2018 that found a similarly unique situation of low CPR and low TFR in Pekalongan Municipality. These results indicate an unusual prevalence of contraceptives in the urban setting.

Data anomaly in FP interventions may also be the result of error in data collection. Nortman and G. Lewis (1984) elaborated many kinds of significant data incongruence in their study. For example, there was a high percentage of couples who expressed their preference to not bear another child, yet low percentage of CPR. This phenomenon was also found in the urban setting. Additionally, in Surakarta, we found low prevalence rate of long-acting contraceptives at 31.32 per cent, which could lead to the data anomaly. With FP participant population dominated by acceptors of short-acting contraceptives, the rate of participation of drop-out (DO) becomes more likely to increase. The Annual FP Evaluation Report of Surakarta’s Population Control and Family Planning Office revealed a significant increase of FP drop-outs from 2018 to 2019, namely by 2,983 or 64.19 per cent of new contraceptive acceptors per December 2019.

The belief regarding the ideal number of children in families further contributed to Surakarta’s low TFR. The number of children among women of childbearing age has direct correlation to contraceptive use, as evidenced by a study of Choe & Tsuya (1991), which found that women’s contraceptive use behavior depended on the number of children they had. Another analysis showed that with more children, the likelihood for women to use contraceptives was also greater (Resti Pujihasvuty, 2017).

Other factors that could contribute to FP data anomaly in Surakarta are human resource and local policy on FP. FP interventions can be delivered optimally under a reasonable ratio of FP extension officer to number of areas served. Meanwhile, local policies that support FP interventions can make the program more effective. Full support from the local government can push the program towards its intended goal, namely low TFR and high CPR.

Based on the results of data analysis of this study, we propose the following activities that may be taken up as part of FP interventions, especially in regions in quadrant 3 of low TFR and low CPR:

- Capacity building of staff, especially staff of FP program.

- Optimizing FP services by promoting long-acting contraceptives after childbirth and miscarriage.

- Designing interventions for strategic target segments based on household-level data collection by name and by address.

- Optimizing FP advocacy and communications, especially on delaying age at first marriage for youth.

- Carrying out advocacy targeting different cross-sector stakeholders/strategic partners, such as the Religious Affairs Ministry, the Youth and Sports Office, and the Education Office.

- Designing innovative advocacy methods for couples of childbearing age.

- Approach middle- and upper-class couples by making home visit to promote FP program.

CONCLUSIONS

- Population and family planning issues in Surakarta are not exclusively technical issues, but are also contributed by the belief and perception about contraceptives.

- Low CPR and low TFR may be caused by inaccuracies in data collection, or because the data collected are not sufficient to represent a population. This may be caused by untrained enumerators or psychological stress tied to the demand of covering new participants, which eventually compromise data accountability.

- The diverse make-up of Surakarta’s population in terms of ethnicity, religion, education, and socio-economic status presents a significant challenge in FP delivery.

- FP program must get the support of stakeholders – media, political parties, etc.

RECOMMENDATIONS

1.For Surakarta Municipality government

-

- Promote population-oriented development as a strategic issue in Surakarta.

- Expand budget support for family development, population, and family planning program.

2. For heads of districts, sub-districts, and rural-level institutions such as LPMK (Rural Community Empowerment Institution)

Increase their support and commitment to family development, population, and family planning program through various local activities.

3. For academia, civil-society organizations, and cross-sectoral stakeholders

Universities, CSOs, and cross-sectoral stakeholders are expected to provide tangible contribution to family development, population, and family planning program to ensure the program’s success and benefit for the people.

REFERENCES

Adioetomo, S.M., 1993. “Construction of Small-Family Norm in Java”. Unpublished Ph.D thesis. Australian National University, Canberra Australia.

Ananta, A., Lim, T., Molyneaux, J.W., & Kantner, A. (1992). Fertility determinants in Indonesia: A sequential analysis of the proximate determinants. Majalah Demografi Indonesia, 37, 1-26.

Arikunto, Suharsimi. (2012). Prosedur Penelitian Suatu Pendekatan Praktek. Jakarta: Rineka Cipta.

Arum, Dyah, N.S., dan Sujiyatini. 2016. Panduan Lengkap Pelayanan KB Terkini. Yogyakarta: Nuha Medika.

Basu, M.A., 2007. “Ultramodern Contraception: Social Class and Family Planning in India”. Asian Population Studies,1, pp. 303-323.

BKKBN. 2019. Laporan Kinerja Tahun 2019. Semarang: BKKBN Jawa Tengah

BKKBN (Badan Kependudukan dan Keluarga Berencana Nasional/National Board of Population and Family Planning Central Java Province). 2015. Family Data Collection in 2014.

Bongaarts, J., W. P. Mauldin, and James F. P. 1990. “The Demographic Impact of Family Planning Programs”. Studies in Familiy Planning, 21 (6), pp 299-310.

Bruce, J., 1990. “Fundamental Elements of the Quality of Care: A Simple Framework.” Studies in Family Planning, 21. (2), pp. 61 – 91.

Choe, M.K. & Tsuya, N.O. (1991). Why do Chinese women practice contraception? The case of rural Jilin Province. Studies in Family Planning, 22(1), 39-51. doi: 10.2307/1966518

Davis, K. & Blake, J. (1956). Social structure and fertility: An analytic framework. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 4(3), 211-235. doi: 10.1086/449714.

Dinas Kesehatan Provinsi Jawa Tengah. 2019. Profil Kesehatan Jawa Tengan 2019. Semarang: Dinas Kesehatan Provinsi Jawa Tengah.

Hedrina Emi. 2011. Faktor determinan unmet need suatu studi di kelurahan kayau kubu kecamatan Guguk panjang kota Bukit Tinggi, https://pasca.unand.ac.id

Hermalin, A. I. and Barbara E., 1985. “Future Directions in Analysis of Contraceptive Availability.” in International Population Conference, Florence, 3, pp. 445-456. Jain, A.K., 1989. “Fertility Reduction and the Quality of Family Planning Service”. Studies in Family Planning, 20 (1), pp 1–16.

John Hopkins University [JHU], BKKBN, UGM, UNHAS, & USU. (2016). Draft full report PMA2020. Jakarta: JHU, BKKBN, UGM, UNHAS, & USU.

Nana Syaodih Sukmadinata (2009). Metode penelitian Pendidikan. Bandung: Remaja Rosdakarya.

Nortman D. and G Lewis., 1984. “ A Time Model to Measure Contraceptive Demand”. Survey Analysis for the Guidance of Family Planning Programs. J Ross and McNamara (eds). Ordina Editions. pp. 37-47, Liege Belgium.

Resti Pujihasvuty. 2017. Profil Pemakaian Kontrasepsi: Disparitas Antara Perdesaan Dan Perkotaan. Jurnal Kependudukan Indonesia | Vol. 12 No. 2 December 2017 | 105-118.

Saratri Wilonoyudho, Sucihatiningsih Dian Wisika Prajanti. 2018. Anomalies in Family Planning in Central Java, Indonesia. International Journal of Indonesian Society and Culture 10(1) (2018): 86-91. Semarang: Universitas Negeri Semarang.